Jane A. Flegal, University of California, Berkeley and Andrew Maynard, Arizona State University

Hollywood’s latest disaster flick, “Geostorm,” is premised on the idea that humans have figured out how to control the Earth’s climate. A powerful satellite-based technology allows users to fine-tune the weather, overcoming the ravages of climate change. Everyone, everywhere can quite literally “have a nice day,” until – spoiler alert! – things do not go as planned.

Admittedly, the movie is a fantasy set in a deeply unrealistic near-future. But coming on the heels of one of the most extreme hurricane seasons in recent history, it’s tempting to imagine a world where we could regulate the weather. Despite a long history of interest in weather modification, controlling the climate is, to be frank, unattainable with current technology. But underneath the frippery of “Geostorm,” is there a valid message about the promises and perils of planetary management?

Fiddling with our global climate

The technology in the movie “Geostorm” is laughably fantastical. But the idea of technologies that might be used to “geoengineer” the climate is not.

Geoengineering, also called climate engineering, is a set of emerging technologies that could potentially offset some of the consequences of climate change. Some scientists are taking it seriously, considering geoengineering among the range of approaches for managing the risks of climate change – although always as a complement to, and not a substitute for, reducing emissions and adapting to the effects of climate change.

These innovations are often lumped into two categories. Carbon dioxide removal (or negative emissions) technologies set out to actively remove greenhouse gases from the atmosphere. In contrast, solar radiation management (or solar geoengineering) aims to reduce how much sunlight reaches the Earth.

Because it takes time for the climate to respond to changes, even if we stopped emitting greenhouse gases today, some level of climate change – and its associated risks – is unavoidable. Advocates of solar geoengineering argue that, if done well, these technologies might help limit some effects, including sea level rise and changes in weather patterns, and do so quickly.

But as might be expected, the idea of intentionally tinkering with the Earth’s atmosphere to curb the impacts of climate change is controversial. Even conducting research into climate engineering raises some hackles.

AP Photo/Channi Anand

Global stakes are high

Geoengineering could reshape our world in fundamental ways. Because of the global impacts that will inevitably accompany attempts to engineer the planet, this isn’t a technology where some people can selectively opt in or opt out out of it: Geoengineering has the potential to affect everyone. Moreover, it raises profound questions about humans’ relationship to nonhuman nature. The conversations that matter are ultimately less about the technology itself and more about what we collectively stand to gain or lose politically, culturally and socially.

Much of the debate around how advisable geoengineering research is has focused on solar geoengineering, not carbon dioxide removal. One of the worries here is that figuring out aspects of solar geoengineering could lead us down a slippery slope to actually doing it. Just doing research could make deploying solar geoengineering more likely, even if it proves to be a really bad idea. And it comes with the risk that the techniques might be bad for some while good for others, potentially exacerbating existing inequalities, or creating new ones.

For example, early studies using computer models indicated that injecting particles into the stratosphere to cool parts of Earth might disrupt the Asian and African summer monsoons, threatening the food supply for billions of people. Even if deployment wouldn’t necessarily result in regional inequalities, the prospect of solar geoengineering raises questions about who has the power to shape our climate futures, and who and what gets left out.

Other concerns focus on possible unintended consequences of large-scale open-air experimentation – especially when our whole planet becomes the lab. There’s a fear that the consequences would be irreversible, and that the line between research and deployment is inherently fuzzy.

And then there’s the distraction problem, often known as the “moral hazard.” Even researching geoengineering as one potential response to climate change may distract from the necessary and difficult work of reducing greenhouse gas levels and adapting to a changing climate – not to mention the challenges of encouraging more sustainable lifestyles and practices.

To be fair, many scientists in the small geoengineering community take these concerns very seriously. This was evident in the robust conversations around the ethics and politics of geoengineering at a recent meeting in Berlin. But there’s still no consensus on whether and how to engage in responsible geoengineering research.

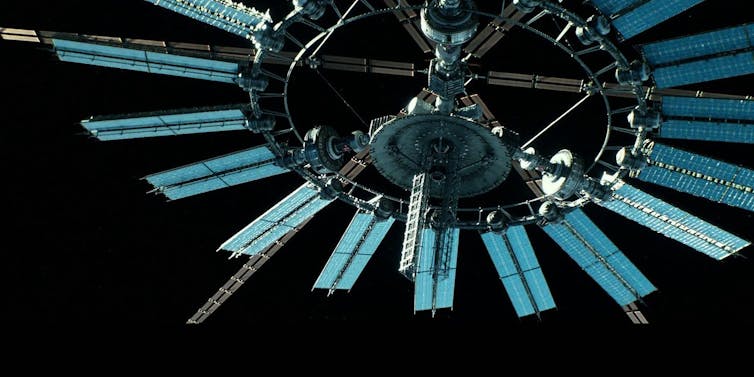

Still from ‘Geostorm’

A geostorm in a teacup?

So how close are we to the dystopian future of “Geostorm”? The truth is that geoengineering is still little more than a twinkle in the eyes of a small group of scientists. In the words of Jack Stilgoe, author of the book “Experiment Earth: Responsible innovation in geoengineering”:

“We shouldn’t be scared of geoengineering, at least not yet. It is neither as exciting nor as terrifying as we have been led to believe, for the simple reason that it doesn’t exist.”

Compared to other emerging technologies, solar geoengineering has no industrial demand and no strong economic driver as yet, and simply doesn’t appeal to national interests in global competitiveness. Because of this, it’s an idea that’s struggled to translate from the pages of academic papers and newsprint into reality.

Even government agencies appear wary of funding outdoor research into solar geoengineering – possibly because it’s an ethically fraught area, but also because it’s an academically interesting idea with no clear economic or political return for those who invest in it.

Yet some supporters make a strong case for knowing more about the potential benefits, risks and efficacy of these ideas. So scientists are beginning to turn to private funding. Harvard University, for instance, recently launched the Solar Geoengineering Research Program, funded by Bill Gates, the Hewlett Foundation and others.

As part of this program, researchers David Keith and Frank Keutsch are already planning small-scale experiments to inject fine sunlight-reflecting particles into the stratosphere above Tucson, Arizona. It’s a very small experiment, and wouldn’t be the first, but it aims to generate new information about whether and how such particles might one day be used to control the amount of sunlight reaching the Earth.

And importantly, it suggests that, where governments fear to tread, wealthy individuals and philanthropy may end up pushing the boundaries of geoengineering research – with or without the rest of society’s consent.

Still from ‘Geostorm’

The case for public dialogue

The upshot is there’s a growing need for public debate around whether and how to move forward.

Ultimately, no amount of scientific evidence is likely to single-handedly resolve wider debates about the benefits and risks – we’ve learned this much from the persistent debates about genetically modified organisms, nuclear power and other high-impact technologies.

Leaving these discussions to experts is not only counter to democratic principles but likely to be self-defeating, as more research in complex domains can often make controversies worse. The bad news here is that research on public views about geoengineering (admittedly limited to Europe and the U.S.) suggests that most people are unfamiliar with the idea. The good news, though, is that social science research and practical experience have shown that people have the capacity to learn and deliberate on complex technologies, if given the opportunity.

As researchers in the responsible development and use of emerging technologies, we suggest less speculation about the ethics of imagined geoengineered futures, which can sometimes close down, rather than open up, decision-making about these technologies. Instead, we need more rigor in how we think about near-term choices around researching these ideas in ways that respond to social norms and contexts. This includes thinking hard about whether and how to govern privately funded research in this domain. And uncomfortable as it may feel, it means that scientists and political leaders need to remain open to the possibility that societies will not want to develop these ideas at all.

![]() All of this is a far cry from the Hollywood hysteria of “Geostorm.” Yet decisions about geoengineering research are already being made in real life. We probably won’t have satellite-based weather control any time soon. But if scientists intend to research technologies to deliberately intervene in our climate system, we need to start talking seriously about whether and how to collectively, and responsibly, move forward.

All of this is a far cry from the Hollywood hysteria of “Geostorm.” Yet decisions about geoengineering research are already being made in real life. We probably won’t have satellite-based weather control any time soon. But if scientists intend to research technologies to deliberately intervene in our climate system, we need to start talking seriously about whether and how to collectively, and responsibly, move forward.

Jane A. Flegal, Ph.D. Candidate, Environmental Science, Policy, and Management, University of California, Berkeley and Andrew Maynard, Director, Risk Innovation Lab, Arizona State University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

A Portuguese translation of this article by Artur Weber is available at homeyou.